It would be an understatement to anyone who reads the news or logs on to social media platforms to say that the 2020 presidential election is top of mind for many Americans. What isn’t so clear, however, is whether or not people will channel that energy into turning out to vote next November. With nearly two-thirds of Americans believing things in our country to be “seriously off track”, at first glance it would seem it’s surprising that voter turnout in US elections is so low. However, history tells us that even when an election is top-of-mind, there are still barriers that prevent people from voting, so we shouldn’t take it for granted that salience will translate to turnout.

The US is ranked 26th of the OECD countries in voter turnout, with only 60% of eligible voters participating in past presidential elections. We think behavioral science can help more Americans cast their ballots, strengthening our democracy. We’re interested in questions such as: What drives people to the polls? What prevents them from following through on their intention to vote? How can we engage the millions of Americans who don’t consistently make it to the voting booth?

During the 2018 midterms, we set out to answer these questions and understand how our interventions can be a force-multiplying tool for the application of behavioral science across the democratic ecosystem. Working with non-profits and state governments, we designed and tested a series of voter outreach materials leading up to the midterms, ultimately reaching over 4 million potential voters. These efforts generated meaningful insights about what works to motivate voters across contexts, providing an exciting foundation for our continued work in 2020 and beyond.

Reframing what it means to be a ‘good voter’

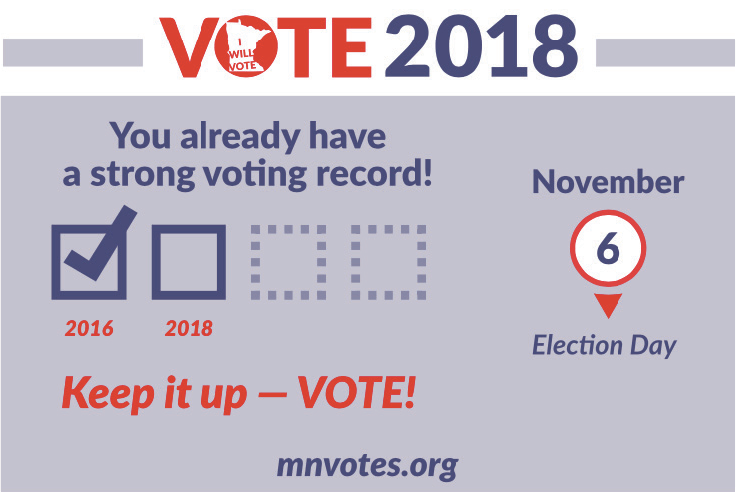

In Minnesota, we partnered with the office of the Secretary of State to develop solutions to increase turnout for “drop-off voters” (those who only vote in presidential elections) and other occasional voters. Our goal was to help more people develop a consistent habit of voting. We knew state administrators could be an important channel for this type of voter outreach since they are a trusted source for official information and already have a number of touchpoints with potential voters. Leveraging the power of this channel, we designed and tested simple postcards that addressed key barriers occasional voters may face: an incorrect mental model of what it means to be a good voter, lack of accountability for voting, and a lack of a strong voter identity. Our strongest intervention used positive social pressure to increase turnout by nearly 0.5 percentage points, or about 860 more votes in our sample size.

Driving environmentalists to the polls

With the Environmental Voter Project (EVP), a non-profit that aims to help more environmentalists vote, we tested different types of message framing, the timing of reminders to vote, and various channels of communication to understand how to reach and motivate EVP’s target population – low-propensity voters who are likely to prioritize environmental issues. By running multiple treatment groups, we found that text messages, direct mail, and digital ads can all be highly cost-effective channels for increasing turnout, especially when combined with thoughtful behavioral design. Our outreach messages which leveraged social accountability and the human desire to be internally consistent between our intentions and actions increased turnout by .14-1.22 percentage points, or about 2,400 additional votes generated.

Turning out young voters

We also worked with TurboVote, an organization that provides election information and reminders to a large group of tech savvy-youth in the electorate. Partnering with TurboVote gave us an exciting opportunity to optimize an already effective voter outreach infrastructure (characterized by an efficient series of reminders) that reaches a diverse subset of the overall electorate. Together, we tested messages and reminders that centered on plan-making and increasing the social aspects of voting by emphasizing social influence, accountability, and the possibility for social exclusion. In the 2018 primary elections, our plan-making messages increased turnout by nearly half a percentage point and in the general election, our social accountability messaging increased turnout by a quarter of a percentage point.

Working across this set of partners and testing with rigorous impact evaluations, our efforts in the 2018 cycle highlight the role behavioral science can play in driving cost-effective increases in voter turnout. It also shows the broad potential to integrate behavioral science into the democratic ecosystem. 2018 set a record for participation in a midterm election, but 100 million eligible Americans still did not cast a vote, which means there is more work to be done.

Moving forward, in the 2020 election and future cycles, we are planning to use what we have learned to deepen and scale these insights to work with more partners across more channels. We plan to continue building and maintaining strong partnerships across the country to further integrate behavioral science into the election infrastructure by working with some of the most exciting election reforms to date, including automatic voter registration and flexible Vote-at-Home policies wherever possible. We will continue to be laser-focused on how to energize and engage nonvoters, guide new voters to the polls, and increase the turnout rates of occasional voters.

With concerted efforts across the country, 2018’s record-breaking turnout could be seen someday as an inflection point between America’s low-turnout past and a future of marked by robust democratic participation by all in the U.S.