At ideas42, we’re becoming accustomed to welcoming several days of excitement around this time of year, for reasons that have very little to do with the crispness in the air or the changing colors of the foliage, and very much to do with happenings in faraway Stockholm. We speak, of course, of the annual announcement of the Nobel Prize for Economics (or, more properly, the The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2019).

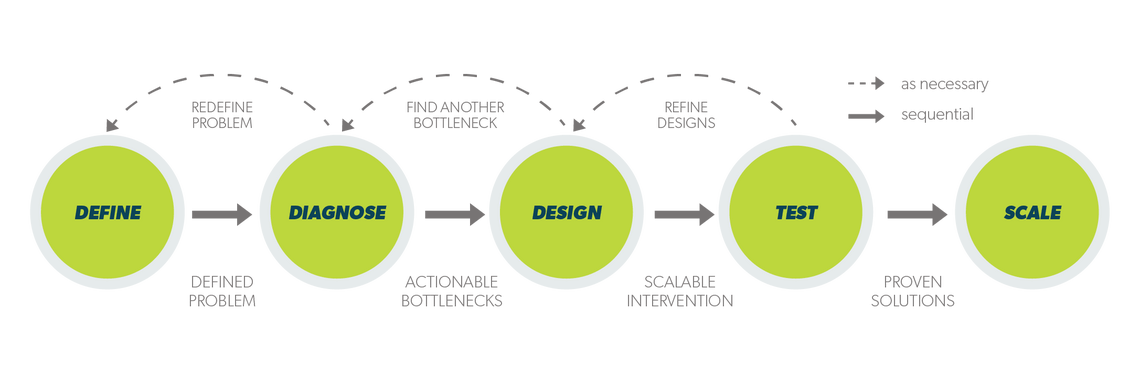

Two years ago, it was the turn of one of our mentors, and founders of behavioral science, Richard Thaler, to be honored. The insights Richard’s work generated—from mental accounting to satisficing to the endowment effect (among others)—are of course the central piece of what we do at ideas42, where we apply behavioral science to knotty problems in fields ranging from financial health to climate change to civic engagement (among others). Within our own methodology, his work is central to the second “D” – Diagnosis, and also the third – Design.

The link with this year’s prize may not be as immediately apparent, but in fact the methods of rigorous evaluation for which Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer have been honored are the basis for the “T” in our methodology. At ideas42, we seek to run randomized control trials of every intervention we design, because we know that many things that ought to ‘work’ don’t, and that figuring out whether something truly happened because of an intervention we designed, or whether it would have happened anyway, is difficult.

This is why we use RCTs, whose use in development and policy evaluation was pioneered by this year’s Nobel winners, to measure the impact of our interventions. But we’re not just users of these methods – we’ve also been trying to adapt them to make them quicker, leaner, and more iterative—for example by focusing on short-term outcomes for which there are good administrative data. Recently, we’ve run RCTs on beneficiaries of cash transfer programs in Kenya and Tanzania, and found promising signs of improved financial behaviors. But we’ve used RCTs in many, many different contexts and for many kinds of issues, ranging from water conservation in Costa Rica, to electricity use in Cape Town, to improved educational outcomes in colleges in the US, to the uptake of family planning methods in Nepal. In each case, carefully designed RCTs have helped us figure out whether the intervention we designed work—and if so, how well.

So of course, we are beyond excited to see the research that in many critical ways allows us to do the work we do honored in such a prestigious way—twice in three years! Join us in congratulating Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer, and may many more (nimble, low-cost, behaviorally informed) RCTs bloom!