Behavioral science provides a crucial framework for understanding human responses to uncertainty. As we unpacked in a recent post, we’ve all been living with high levels of uncertainty and instability throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

When it comes to uncertainty regarding COVID-19 vaccines, there are four “cognitive pitfalls” in particular that are likely to affect decision-making. In the previous post, we examined the first two: ambiguity aversion and the possibility and certainty effects. Here, we take a look at the next two pitfalls.

With these cognitive tendencies in mind, healthcare practitioners and others who communicate about vaccines can help people overcome these pitfalls, to protect themselves, their families, and their communities from COVID-19.

Zero Risk Bias

We like to take actions that completely eliminate one kind of risk, even if it increases our overall exposure to a negative outcome. This is known as zero risk bias. Remember all that panicked toilet paper buying in early 2020? It’s a great example of the zero risk bias in action. Rushing to a crowded grocery store to stock up on toilet paper eliminates your risk of a tricky situation in the bathroom, but in aggregate it exposes you to a much worse risk of contracting a potentially deadly disease. In this case, people were opting to reduce their bathroom risk to zero, and in doing so neglect the broader category of COVID-19 related risks.

Getting vaccinated against COVID-19 lowers risk of becoming infected, particularly the chances of severe illness leading to hospitalization or death. But vaccines don’t entirely eliminate those risks, and they also introduce another possibility–experiencing side effects. Avoiding the vaccines eliminates that risk of side effects. Essentially, people may accept a much higher risk of getting COVID-19 if it allows them to eliminate another category of risk, even though the levels of those two risks are very different.

One approach to address this bias is to find ways to eliminate categories of risk relating to vaccination, such as guaranteeing paid sick leave so people won’t need to risk income loss if they experience side effects. Another is to reframe how people are conceiving risks, shifting the focus away from contracting COVID-19 to more serious outcomes like hospitalization or death. While vaccines will not eliminate your possibility of contracting COVID-19 or even coming down with symptoms, early evidence around the Omicron variant suggests that a recent booster shot all but eliminates the risk of serious illness and death for otherwise healthy people.

Attribute Substitution and Negativity Dominance

Objectively evaluating the odds of catching COVID-19 is hard (especially with each new variant bringing different rates of transmissibility), to say nothing of assessing how severe the illness might be. A much easier question to answer might be, “how many people do I know who got COVID-19, and how serious was their illness?” When confronting hard-to-evaluate questions, our brains tend to substitute easier questions like these to help us navigate complexity and uncertainty. This cognitive process is known as attribute substitution. Like the other biases, while it often serves us well in making quick judgments, it can lead us astray when evaluating risks and benefits around COVID-19 vaccines. And when we are evaluating these risks, our thinking tends to be biased even further by negativity dominance, which is the tendency to give more weight to negative events and information relative to positive.

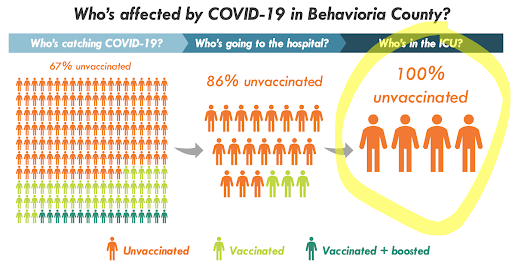

To counter these effects, vivid and intuitive graphics (such as the example for an imaginary “Behavioria County” below) showing the tiny scale of breakthrough infections that lead to hospitalizations and deaths compared to the magnitude of total vaccinations can be effective. This visual would make it easier for our brains to process just how rare serious infections among vaccinated individuals are, better highlighting the positive benefits.

Throughout the pandemic, a core component of public health messaging has depended on the assumption that people calculate risk and probability effectively and then make informed choices about whether or not to get the COVID-19 vaccine or any boosters. But as the four cognitive pitfalls we’ve discussed in this series show, it’s very easy for anyone to be swayed by psychological biases. When systems are designed around assumptions about human behavior that don’t hold true, it’s a failure of the system, not of the person doing their best to navigate it. As behavioral scientists and practitioners, we need to make sure that we’re meeting people where they are, and working to ensure that our messaging and systems account for the ways people actually think and behave.