Aside from providing us with wages and spending power, work is a vehicle for social cohesion, aspirations for growth and a feeling of self-worth. In a world where 95% of the total labor force is technically employed, it can be hard to believe that as many as 300 million people have paid work but live below the international poverty line of $1.90 a day, and 42% of workers worldwide (1.4 billion) are in vulnerable forms of employment—work with inadequate hours or earnings, low productivity, and/or difficult work conditions.

Active labor market programs (ALMPs) are theoretically meant to help connect workers to more and better employment. They do so by providing skills trainings, job matching services, and entrepreneurship programs. But are these programs producing as much impact as possible? We reviewed outcomes from recent studies of labor market programs and found that many of them suffer from two of the most prevalent problems we currently address with behavioral science: low take-up by those who stand to benefit the most from the programs, and low persistence rates.

As an extension of our existing poverty alleviation and social protection work, ideas42 is partnering with non-profit organizations, governments and multilaterals around the world to generate new insights about ways we can use behavioral science to improve labor market programs.

We started with an examination of the rationale for ALMPs, identified the two common problems faced by ALMPs (low take-up and low persistence rates) and uncovered programmatic design aspects and features of the context that may be leading to these problems. We’re excited to share the resulting insights and broad initial recommendations for scalable solutions rooted in behavioral science in our new white paper: Better Choices, Decent Work: Using Behavioral Design to Improve Labor Market Programs in Low and Middle-Income Countries. It contains a path to removing the often-overlooked barriers that can hinder people from taking up and following through on leveraging beneficial labor programs.

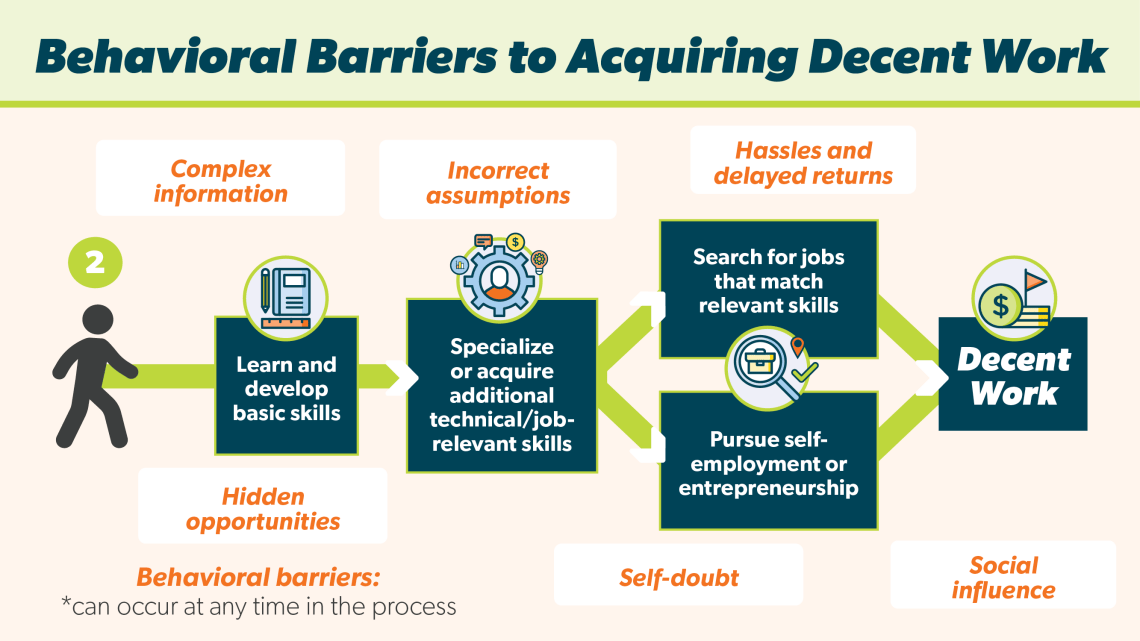

What are some of these barriers? First, by their very nature, the benefits of ALMPs are usually not felt until months or years later. However, just to get started, participants have to go through a process comprised of multiple steps: registration, selecting appropriate services, and following through on requirements before having a chance to secure employment. They’re bearing short-term costs when the most significant returns, such as higher income and more job growth, will occur in the distant future.

When the immediate costs of starting a program, such as time and opportunity costs, are most salient, it’s easy to imagine that long-term benefits may be underweighted, tempting participants to either give up and seek seemingly easier, but less effective, pathways to employment.

This alone makes it understandable that many people may struggle to persist on the path to reaping the benefits of an ALMP, but there’s more. Faced with decisions about which services and how many to pursue in the first place, people may rely on vague assumptions or the visible actions of their peers to make decisions. It’s also clear how such ambiguity or challenges along the way can lead to feelings of self-doubt, especially when one takes into consideration that ALMPs tend to support individuals experiencing high rates of poverty and vulnerability, which only compounds challenging situations.

The good news is that there is significant potential for effectively applying a behavioral lens to ALMPs in support of participants along this journey. And many of the potential changes are relatively low-lift to implement.

For example, program designers can easily simplify labor market information and make the benefits of some overlooked work opportunities more salient in their communications to potential participants. Reframing such opportunities and making desired decisions and actions more visible could directly address preexisting assumptions about available career paths that have deterred specific groups from considering beneficial options in the past.

To encourage follow-through, program designers could ‘audit’ their current processes and identify ways to reduce unnecessary hassles wherever possible. In addition, they can create resources that help beneficiaries overcome the barriers that remain, all while continuing to make ALMP long-term benefits more salient in the present. Lastly, efforts to remind beneficiaries of their own capabilities and locus of control (a strategy which has improved performance in education outcomes for marginalized populations in past interventions) can be adapted and utilized in labor market programs.

These insights (and others in Better Choices, Decent Work) are just an initial foray into this space. Our next step is to partner with those who can help us test our recommendations, generating evidence about the most effective strategies that ALMPs can use to reach more beneficiaries, help more people acquire decent work, and most importantly, improve livelihoods around the world.

To learn more, read the full paper, or write to us at livelihoods@ideas42.org if you are working toward a similar goal and would like to partner with us.