An unplanned pregnancy during adolescence can dramatically impact a girl’s health and economic future, yet use of modern family planning (FP) services among adolescents remains low in many places. The challenge is particularly great in many countries in Africa, where despite a global rise in FP use among adolescents, adolescent fertility remains high and nearly two-thirds of sexually active girls who want to avoid pregnancy are not using a modern contraceptive method. Access to modern contraceptives is hindered by a variety of factors, including legal barriers like age of consent, affordability, method availability, and health workers’ willingness to provide sexual and reproductive health services to youth. But even when these obstacles are overcome, uptake of FP services often remains low.

Efforts to tackle the challenge often focus on improving the availability and ‘youth-friendliness’ of services, educating girls about FP and encouraging them to access services, and convincing communities that youth access to modern contraceptives is important. While programs sometimes work through peer educators to reach youth, these young people are often trained extensively and take on a more formal role, in contrast to the girls they seek to reach, who are approached as more passive recipients or beneficiaries of such a program rather than true peers. Historically, peer education programs have had limited success.

How, then, can we support girls who wish to avoid an unplanned pregnancy? One answer may lie in the role that girls are asked to play in programs that seek to reach them. Research has repeatedly shown that across many contexts, girls often don’t perceive themselves to have agency in matters concerning sex, family planning, and their reproductive futures. They might be physically able to visit a clinic and take up a family planning method, but they don’t feel confident making the choice for themselves or empowered to act on it. To enhance a sense of agency among girls, we drew from research in other contexts showing that giving advice to others can encourage action by building confidence and motivation. With this in mind, we sought to develop solutions which would put more girls in the role of advocates for family planning within their peer groups.

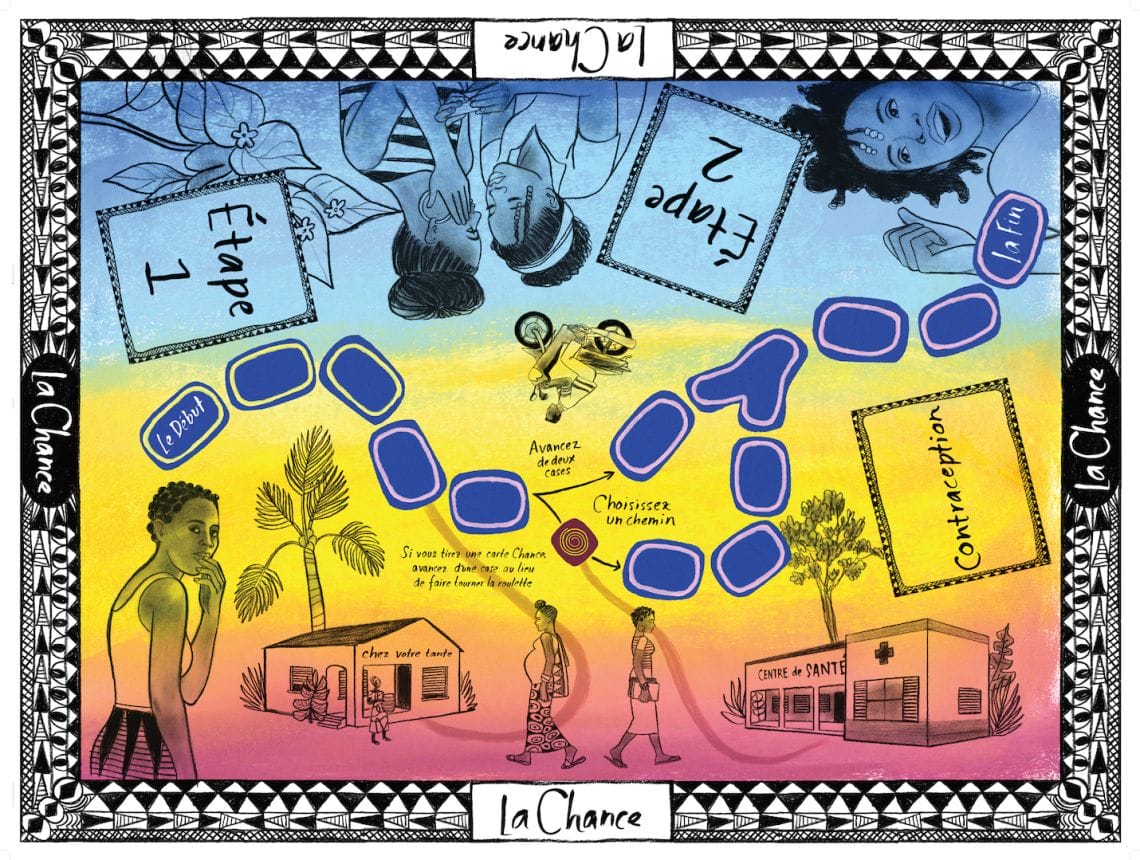

In Burkina Faso, we partnered with Pathfinder International as part of the (re)solve project to design a board game for high school students called La Chance. As they play, girls encounter real-life relationship scenarios, “experience” consequences, and are prompted to share advice. Going through this experience with their classmates, players can begin to understand that other girls like them are both at risk for unplanned pregnancy and can make the choice to access and use FP methods. Players may pick “advice” cards which ask them to provide guidance to other girls on how they should manage difficult relationship situations, or to educate friends that simply knowing and tracking your menstrual cycle may not protect you from pregnancy. We designed the game cards so that players read questions aloud to the rest of the group, and then reveal answers that are visible only with a pair of decoder glasses. This ensured that girls were being engaged as advisors, rather than only listening to messages from authoritative game facilitators. At the end of the game, girls are given multiple “passport” booklets to encourage them and their friends to visit health facilities.

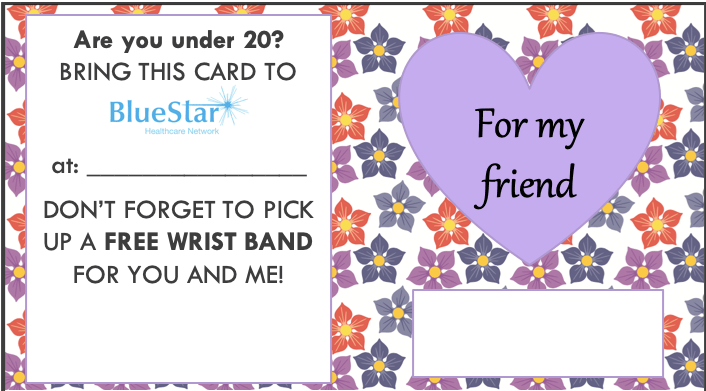

In Uganda, through a collaboration with Marie Stopes, teenage girls receive “Refer-a-Friend” cards from a community-based mobilizer or FP service provider, on which they mark their own motivations for using or learning about family planning. They are then prompted to give the card to a friend and suggest that she also learn more about family planning by visiting a Marie Stopes clinic. At the clinic, each card can be redeemed for two friendship wristbands – one for the girl visiting the clinic and the other for the friend who referred her. Girls are not required to take up an FP method either to give a Refer-a-Friend card or to receive the wristbands. This program offers girls an immediate motivation to talk to friends about family planning, share advice, and articulate reasons why girls like them may choose to use family planning. Girls who receive Refer-a-Friend cards get an endorsement from a trusted peer, while girls who give the cards have an opportunity to give advice that builds their confidence and solidifies their motivation to access FP services when they need them. When a girl visits a clinic to redeem a card, she receives a new card to give to another friend, becoming an advice-giver herself.

Both of these novel programs were designed with girls’ agency in mind–placing them as both active participants in and as recipients of the program. Additionally, both interventions include changes to the facility environment, such as youth-friendly posters and provider training that aim to make health facilities more welcoming environments for girls who have decided to visit. Initial feedback – from girls and from those responsible for administering the programs – has been positive. Both programs are currently being evaluated to assess their impact on volume of adolescent clients at participating clinics (in both countries), intention to use FP (in Burkina Faso), and FP takeup (in Uganda), and we look forward to sharing results when they are available.

Stay tuned for more insights from our work to put every girl and woman in control of their own reproductive health. Questions? Reach out to us at GH@ideas42.org.