As part of our yearlong celebration of our 15th anniversary, we’re reflecting on our journey, our greatest impact, where we’re going, and more about the how that makes us who we are: applying behavioral science for social good.

At ideas42, our goal is—and always has been—to improve millions of lives. In that goal, we are joined by a large community of like-minded practitioners, policymakers, and other problem solvers. But what makes us unique is how we seek to achieve this goal.

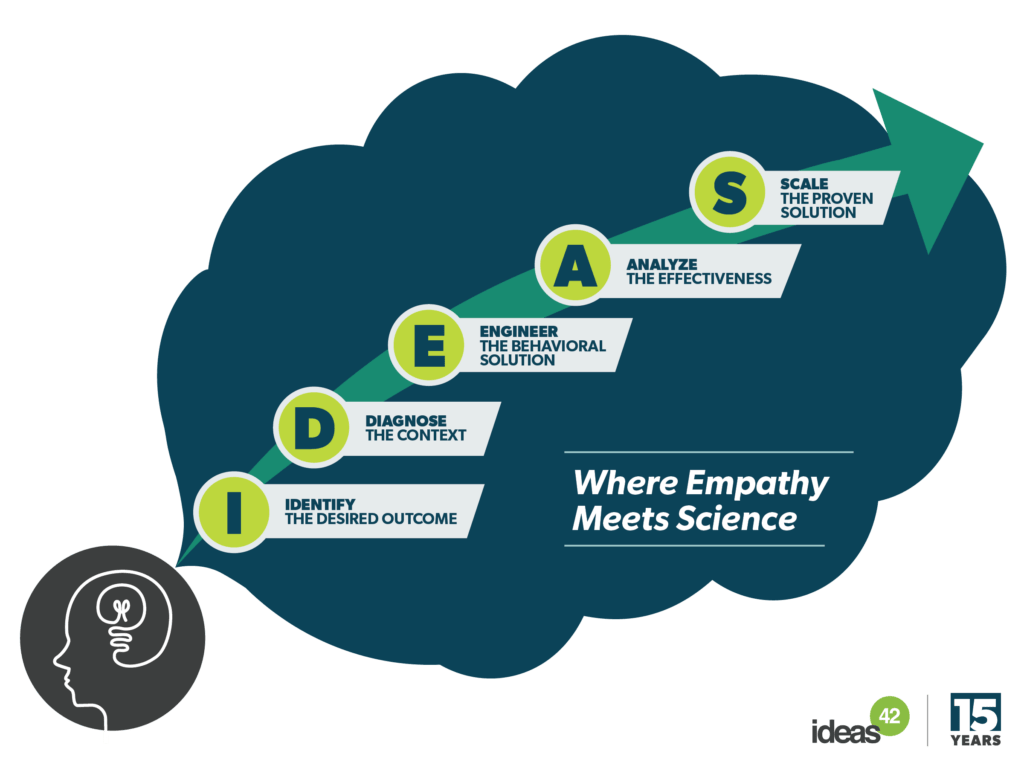

And that how, specifically, is our methodology. We call it behavioral design—the process that underpins all of our solutions, no matter the field or issue area. If you’re unfamiliar with behavioral design, or behavioral science, read on for a primer on our approach.

Behavioral design encapsulates the approach we’ve taken since our founding. We have refined it, and refined it again, through more than 600 projects in over 55 countries so far—helping first generation students persist in college and graduate on time, reducing maternal deaths during childbirth, helping people avoid jail and its disruptive effects for low-level offenses, and mitigating extreme poverty by improving the effectiveness of cash transfer programs in the Global South.

With behavioral design, we endeavor to combine empathy with science at every stage. We begin by identifying the outcomes that are important to the community and partner organizations we are working with. Then we diagnose what might be getting in the way of (or helping drive) those outcomes. In this, behavioral design draws on several of the principles found in human-centered design, which prioritizes the perspectives and needs of its users, and involves immersing oneself in users’ experiences through ethnographic techniques. We also strive to attract team members to ideas42 who share the lived experiences of those we are designing for. Yet behavioral design goes further.

Behavioral design is grounded in insights about human behavior drawn from the deep well of evidence produced by the world’s leading behavioral science researchers. The field itself taps into decades of research spanning psychology, neuroscience, and economics. Since many intricacies of human behavior are unconscious (and can’t be teased out through self-reporting), drawing on behavioral research is critical.

We work with our partners to engineer solutions that fit their community’s needs and preferences. We believe that makes our designs easier to scale. Our goal is always to design solutions that help people make the best decisions for themselves, and are also feasible to implement.

And because even the most promising, well-intentioned solution is only effective if it, well, works, to achieve the desired outcome, behavioral design includes rigorous evaluation—which is not always built into human-centered design. ideas42 leverages robust impact evaluation—such as randomized controlled trials and other experimental methods—whenever possible to measure the effectiveness of our solutions. Finally, we scale the solutions that work.

In sum, 15 years of honing our approach has yielded an evidence-informed, people-centric framework that is responsive to the varied contexts and communities in which we operate.

So what does this look like?

1. Identify the desired outcome

The first stage begins with identifying the outcome we seek to achieve, and defining it through supporting questions. This means asking questions like: for whom is this important—who is the audience, and what are their needs? How far are we from reaching the outcome? What solutions have been tried before? What constitutes success? The goal is a statement of our desired outcome and a clear definition of an important problem we need to solve to get there.

2. Diagnose the context

Now we generate hypotheses as to the behavioral reasons and context behind why the problem may be occurring. Using a behavioral science lens, we identify and categorize potential hurdles—known as “behavioral barriers”—that could be at play. For instance, if we’re solving for low rate of high school students applying to college, we may consider the role of “choice overload” (when presented with too many choices, people can become overwhelmed and take no action). A solution? Simplify their choices by recommending a smaller selection of acceptable universities.

This phase also requires examining people’s context, which we see as an exercise in empathy. Here, context refers to any element of a particular environment, which includes overt, physical features as well as psychological attributes (including the beneficiary’s mental state—are they tired? afraid? etc.). Whenever we can, we work with those who have lived experience. We conduct qualitative research—participant observation, surveys, and focus group interviews—along with data analysis to examine trends and patterns. We undertake direct observation and data analysis to complement self-reported behavior (such as information obtained through interviews), because so much of people’s decision-making is unconscious.

3. Engineer the behavioral solution

It’s party time! Having identified and organized a possible set of behavioral barriers, now is the time to generate solutions. Often dubbed “interventions,” this may be a new product (or redesign), tweak to a policy or program, or wholesale overhaul of an outdated system. We endeavor to produce a few designs, as they inevitably evolve once put into practice. Our interventions necessarily strike a balance between what we anticipate will have the greatest impact, and practical considerations like budget and timeframe. We co-design with the organizations who will implement the solution so that we can be sensitive to their constraints and capabilities.

4. Analyze the effectiveness

Once we’ve designed our proposed intervention, we usually run some user testing—putting our novel product or approach in the hands of users, observing how they engage with it, and getting feedback. The process almost always uncovers unexpected aspects of the user experience. We may also isolate and test particular components of a more complex design, iterating as we learn. Our goal is to match our users’ preferences and needs as closely as possible while keeping the fundamental behavioral solution at high fidelity.

Next, we field test a concept—conducting one or more experiments (which are generally longer or larger-scale than user testing) to comprehensively analyze its effectiveness. A common method to evaluate behavioral interventions is a randomized controlled trial (RCT). Considered the gold standard for establishing causality, this involves randomly selecting participants to receive either the treatment or a control. Although RCTs tend to be expensive and lengthy, shorter alternatives can produce effective results.

5. Scale the proven solution

If our intervention proves to be effective, the final step is to scale it. While scaling comes at the end, we consider the potential for scaling during earlier stages, and indeed it is a goal throughout the process. We make adjustments to ensure its sustainability and success. Through this approach, even small or seemingly incremental adjustments can have an outsized impact. In practice, this may look like expanding the intervention for use among a larger population, or rolling it out across additional geographies. Because of unique contextual features of any given community or environment, and because effective implementation often requires trusted relationships with local partners, scaling requires careful attention and nuance—what works well within one community or moment in time may not work in another.

In this manner, behavioral design allows us to test whether something works, systematically iterating to maximize effectiveness, while also tapping into the thoughtfulness and creativity of human-centered design.

Taken together, behavioral design sits at the nexus of empathy and science, yielding tremendous potential to solve complex problems and achieve positive social impact.