As behavioral scientists, we know context matters. That’s why in a typical ideas42 project, our team members engage closely with the lived context of real people who will use or be impacted by our designs. We observe how people go about their lives and make daily decisions, interview service providers and people who use these services, meet with program designers and practitioners, and observe the environments in which people interact with the programs and services. Much of this work happens during visits to the field in countries all over the world, as part of our contextual reconnaissance. In addition, evaluating impact of interventions involves surveys or other kinds of data collection.

All this has, of course, changed dramatically since March 2020, when COVID-19 upended the world and the context of our own work, with strict movement restrictions and lockdowns making how we typically do physical interaction untenable. At the same time, our existing knowledge of programs and the ways in which people interact with them became less relevant, as restrictions on gatherings and movement changed the lives of program beneficiaries in a variety of ways. For instance, someone who used to go to a clinic for health care might now obtain the service in a different way – or not at all. Faced with the impossibility (and inadvisability) of travel and the increased importance of understanding people’s new realities – we developed alternative means to get the information we needed to design behaviorally informed programs and services. And, as we do with all our work, we applied a behavioral lens to this new approach.

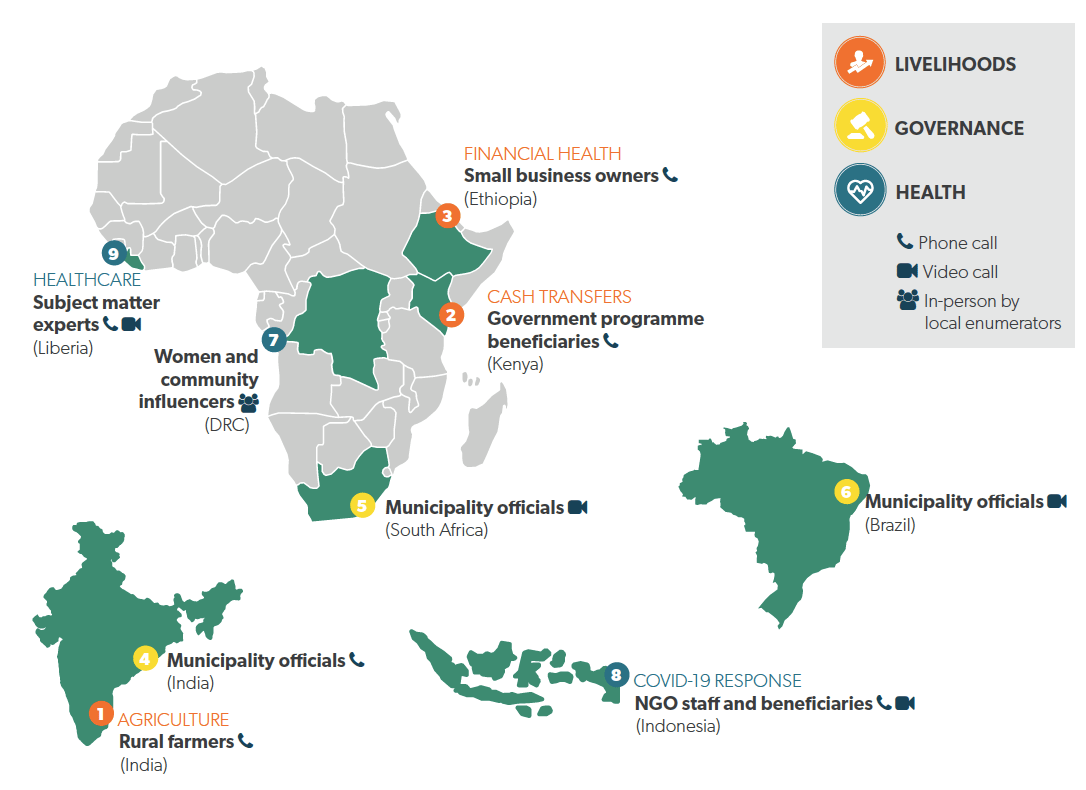

Between March and August 2020, ideas42 teams in our Livelihoods, Governance and Health focus areas, which work across many countries, conducted remote interviews for 10 projects as illustrated below.

The growing availability of basic mobile phones allowed us to connect with a significant portion of target populations. These interviews covered a variety of target populations, including farmers in India, cash transfer recipients in Kenya, small business owners in Ethiopia, community influencers in DRC, and municipality officials in Brazil, India and South Africa. In all, we spoke to people across 8 countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America using voice and video calls – and in one case, by coordinating in-person interviews carried out by local enumerators.

After going through numerous remote working experiences, we’re sharing behavioral insights for making rapid adjustments that researchers doing fieldwork may find useful in these times.

1. Flawed mental models led to planning fallacy

Initially we believed that the time and effort required to conduct interviews remotely instead of in-person would be much lower (due to reduced logistics and eliminated travel). This mental model proved flawed because overall, we needed more resources than anticipated.

Unsurprisingly, flawed mental models led to planning fallacy – we under-budgeted time and resources because we incorrectly assumed that not having to travel would make the process cheaper and faster. Instead, we found that several aspects of working remotely actually require more resources; for example, training enumerators remotely was more time-consuming, especially given the nature of our probing diagnostic interviews.

Strategies to address mental models and to help overcome the planning fallacy

- Make interview guides more structured by reducing the use of discretionary probing questions which are much more difficult to ‘engineer’ remotely, especially when working through an enumerator/third party.

- Build in some “slack” time for unforeseen delays and challenges such as multiple interview rounds or interview breaks, even for plans that seem to account for all activities. This becomes more relevant for remote activities as there are multiple stakeholders across locations and many moving pieces to manage.

- Be adaptable, as some planned activities may prove to be unfeasible – If so, don’t be afraid to eliminate them!

2. Teams experienced cognitive scarcity

Like everyone, our teams are subject to cognitive scarcity, which is magnified when working on multiple tasks across different projects. We realized that an underappreciated aspect of field travel was that it allowed us to focus limited attention and cognitive bandwidth on a specific task (the fieldwork), enabling rapid progress. When we did fieldwork remotely, teams continued to work on their other tasks and projects at the same time, because they could. This results in cognitive overload, exacerbating the effects of limited attention, which can result in teams missing details they would otherwise notice. Furthermore, cognitive scarcity became even more pronounced due to the pandemic, when people juggled home and work responsibilities and also experienced information overload (and stress) about COVID-19 itself.

When we noticed this challenge, we organized remote interviews ‘as if we were in the field’ – blocking out chunks of time to focus on tasks for a single project.

Strategies to manage cognitive scarcity

- If possible, split work between teams to allow individuals to focus undivided attention on one task by blocking particular times (preferably full days) for the task. Consider normalizing the option to decline other competing demands and meeting requests, such as not attending all-team meetings on New York time when focusing on fieldwork on Ethiopia time.

- Create protocols that replicate what you would do in the field: for example, check in at the end of every day’s fieldwork to review and amend any part of the interview process, discuss key insights with team members, and so on.

3. A small token incentive can be helpful, where possible

Respondents may forgo income or work opportunities or incur other costs to participate in remote interviews. For example, erratic electric supply meant that some respondents in rural Kenya walked to locations a distance away from home, where they paid to charge their phones to ensure they could receive the interview call at the scheduled time. We therefore felt it important to compensate them for these direct and imputed costs by means of a token payment for participation. In addition to being the right thing to do, we found that a small incentive led to greater motivation to respond and to stay on the phone during the interview.

Strategies to give incentives

- Ideally, incentives are a small token to compensate respondents, not so large that they influence the decision to participate or responses to survey questions.

- You may Inform participants about the incentive before or after the respondent gives consent for the interview depending on the circumstance. Both strategies worked equally well for us; In Kenya, participants were informed about the airtime incentive after giving oral consent during the interview, and incentives were transferred to them after the interview. In India, participants were informed of the incentive while making an appointment and it was transferred to them before the interview call. Both these projects received similar response rates and most respondents stayed on the calls for the full duration of the interview (30-45 minutes).

- Manage participant expectations, and keep in mind ongoing work; when working with a local partner, you should ideally align the amount and type of incentive to the partner’s typical incentive that they give.

4. Empathize, and be flexible with respondents

Like us, respondents are also facing an unprecedented situation, typically with limited resources. Empathizing and intentionally conveying empathy is important. For instance, ask questions that ensure that participants are comfortable taking the interview at that time, particularly if the questions being asked are personal and sensitive. As most activities have become remote due to COVID-19, interview participants may be fielding calls from a variety of organizations and are talking on the phone much more than before, making fatigue likely. Remembering this and seeking to put people at ease can help ensure more successful interviews.

Strategies to empathize and be flexible

- Establish a connection early during the call by explaining the purpose of the interview and the value of the conversation for them or for people like them. Such efforts go a long way to arouse a sense of reciprocity and make the discussion more meaningful, leading to richer responses and a greater willingness to share relevant incidents and anecdotes, which are particularly useful for designing solutions.

- Use local enumerators who can converse in the local language and understand the context, helping establish rapport through relevant small talk and conversational gambits. Going through trusted sources is helpful to establish credibility, particularly if participants have not already engaged with the organization carrying out the interview.

- Make the timing of the interview flexible, at the convenience of the respondent, and include this flexibility in the project plans. Enumerators may need to call people outside usual working hours, since respondents are often busy in their work during the day. It may also make sense to break interviews up into two parts to accommodate respondents’ schedules, and to be prepared to call back if the initial time proves inconvenient.

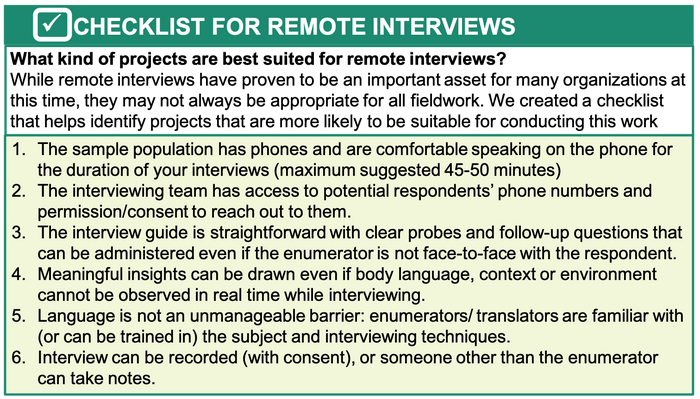

Even with preparation and adaptation, not every remote effort will be feasible and successful. Being realistic about this is critical, as is being open to mid-course changes in strategy. While remote interviews are unlikely to replace the value of connecting directly and meeting stakeholders in person, our experience over these past months has made us appreciate their uses. In fact, there are many situations in which remote interviews could continue to be a widely-used tool even when travel and in-person meetings are safe and possible again.

Have you adapted interviews and data collection methods during the pandemic? Join the conversation and share insights from your work by tweeting at us @ideas42.